Part I: Adam Neumann

In the years after my own foray into a low-stakes-by-comparison-but-still-very-fucked-up scam-centric lifestyle, all I desired was to have a “normal existence.” At the time, that meant fading into obscurity and becoming a corporate lackey (and subsequently, a mostly-law-abiding, functioning member of society). I worked for a lot of companies, sometimes leaving willingly and other times being unceremoniously canned after they figured out who I was. I hadn’t conned my way into these gigs—they had all of my legal information—but whenever they’d get tipped off or google me they would act as if I had. Though all of this corporate ladder-hopping wasn’t great for my psyche, I did get to peek behind the curtain of some of the largest, most influential, most profitable companies in the world.

And baby, all the world’s a (late) stage (capitalistic system)!

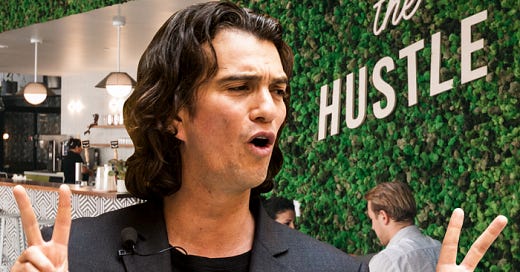

I found myself working with now infamous WeWork founder, Adam Neumann, during the summer of 2015. I had been hired to support WeWork’s Chief Administrative Officer (and eventual CFO)—a buddy of Adam’s that he met during their time serving in the IDF.

It was my first day on the job, and I was getting a tour of the main corporate office in lower Manhattan. As the pleasant HR woman and I navigated through the building, I glanced down a never-ending hallway of offices that made my eyes blur like they do when mirrors are placed across from one another. I imagined we looked like hamsters scurrying through a plastic tube, beady eyes hunting for treats (which luckily were part of the unlimited perks the company liked to tout). We turned a corner and ran directly into Adam Neumann, and his assistant who was trying to rush him into a meeting. We were quickly introduced and shook hands as we exchanged meaningless platitudes—me saying how excited I was to be there, him saying that I should be. He was confident in that flighty privileged neurodivergent immigrant way (real recognize real), but wasn’t particularly charming. Despite his lanky stature, he didn’t have the presence I expected—especially as I had heard of his many daring exploits while he played dutiful disrupter (like tripping balls at company functions). The dude standing in front of me was pretty unremarkable. It’s quite possible that this particular hurried interaction, with a lowly assistant such as myself, didn’t command such a performance, but I digress.

Over my short tenure at WeWork, I quickly discovered how wrong I had initially been. Adam was remarkable. His ability to ideate (for better or worse—one of his first inventions was kneepads for babies) and his work ethic (megalomania?) went unrivaled…Often to the detriment of the employees who didn’t want to stay late to do rails of coke, burning the midnight oil by way of post-nasal drip. Adam was constantly bullying his team for not working hard enough, gaslighting them into 70+ hour work weeks.

But hey, we’ve got beer on tap!

The company was in the throes of a massive surge of growth and at the height of their positive publicity, and had recently received a $10 billion valuation—an astronomical number that exceeded the C-suite’s expectations. WeWork offices (never “WeWorks”) were opening all over the globe. Leadership was also making strong headway on their “groundbreaking” work-live concept. *shudder*

We now all know how disorganized and chaotic the company was, but at the time that wasn’t public knowledge. I was properly shocked by what a true fucking disaster it really was. Adam’s solution to all problems was one I knew all too well: lying to cover up a lie to cover up a lie ad nauseam. But unlike me, Adam had lots of money, so his lies were able to stretch a lot farther.

One day we were in a leadership meeting, Adam’s assistant and I silently taking notes, as they discussed a location in Miami that was set to open at the end of the week. The building was ready to go, outside of one major roadblock—we hadn’t yet secured a Certificate of Occupancy from the fire department. I don’t remember the exact issue, but I think it had something to do with the number of sprinklers required. Whatever the case, the team was scrambling to figure out what to do. We had hundreds of members excitedly awaiting opening day—they had been promised that by joining a family that “did what they loved,” they’d be able to take their own businesses to the next level.

Many potential solutions were tossed around, and most of them required some form of bribery. An executive piped up and said that he had already talked to a local politician, and had been told they weren’t accepting anymore donations at the time. Adam asked what would happen if we sent the money anyway—like, what, they wouldn’t cash that check? I honestly don’t know what happened behind the scenes after that meeting (sorry), but the building opened the following week, only a couple of days late. Not once did I hear anyone in leadership mention the safety or wellbeing of the members or staff.

A few weeks later I was taken into an office and told I was being let go. They didn’t say why, but they didn’t have to. I found out years later, in a New York Mag article, that Adam had “chastised a group of employees for not Googling a job applicant” after finding out that they had hired me. I can just imagine his indignation in that room—how dare his employees not protect him and his assets! How dare they let him get scammed. He wouldn’t have been able to see the great, sad irony of the situation; that his own ego was the only thing that ever made him a victim.

I’m obviously not saying anything new here, and there are far better and more eloquent pieces on WeWork and Adam Neumann. But I did have the distinct dishonor of working with him, up close and personal. It was an education in its own right (if not a fucked up kismet type of thing), and a great way of teaching me exactly what and who I didn’t want to be.

Coming up next, Part II: Vivek Ramaswamy…

Ready for part II, please!